I was interviewed by Twisha Shah-Brandenburg and Thomas Brandenburg for the 5by5 blog. The blog presents five questions and invite five experts to answer them, bringing different perspectives about the same topic. The same questions are asked for different experts, encouraging diversity of thinking and increasing opportunities for dialogue. I am glad to be part of this conversation, as I consider it relevant to advance the field of design.

Question 1

What is the role of design in fostering innovation in the built environment?

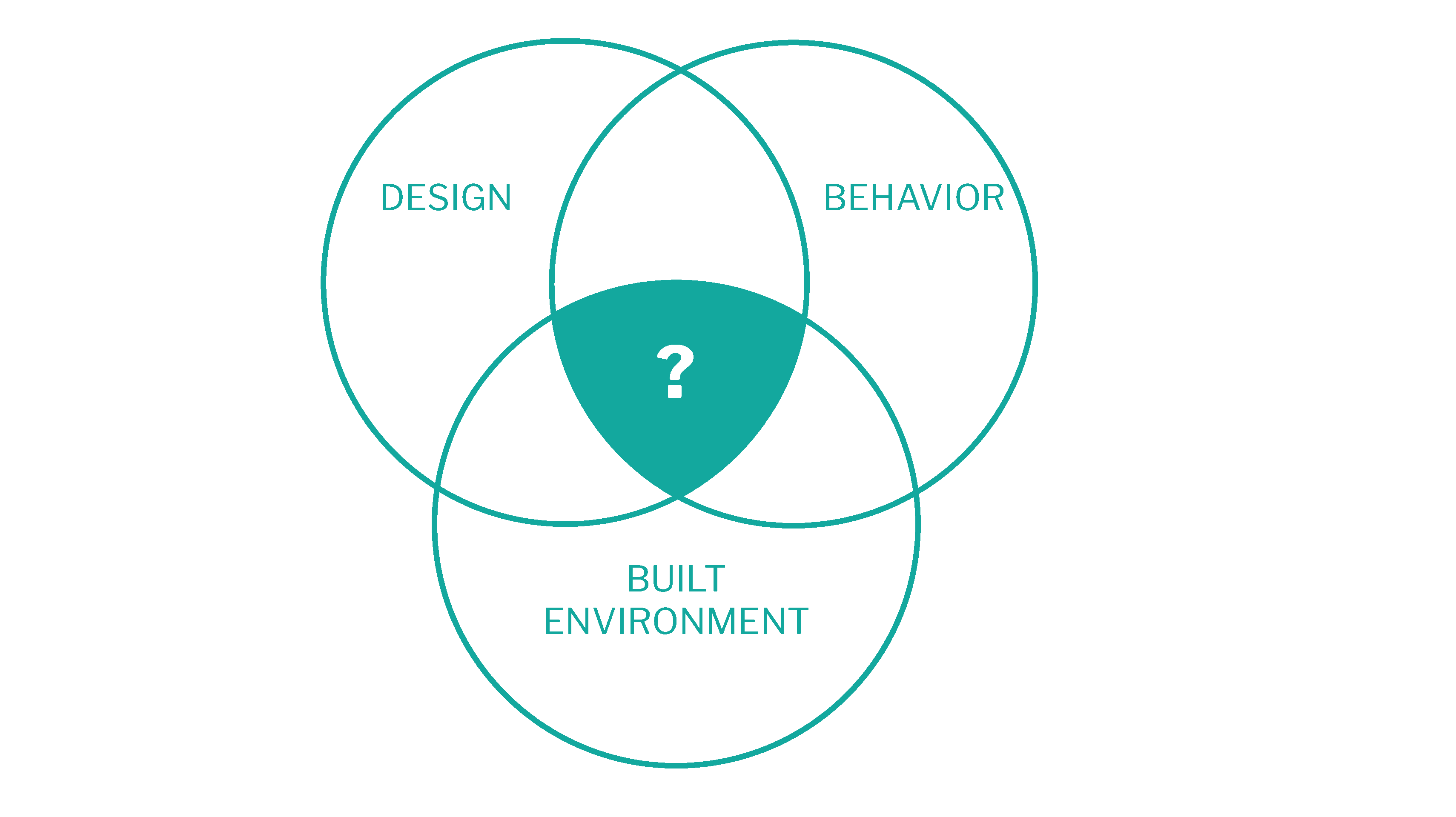

I would like to break this answer into three parts (design, innovation, and built environment), and then integrate them. First, I believe there is no single “role” of design. “Design” has been defined by Herbert Simon as a course of action aiming at contributing to better futures. As a discipline, design can contribute in many ways, especially given the increase of specializations in the field.

Second, innovation can be considered a goal to be achieved which usually in the form of a new offering, but could also be processed. From this perspective, organizations and institutions are encouraged to abandon old paradigms and change their activities (not only their offerings) to bring significant advances into their practices, including the development of new capabilities related to innovation practices.

Lastly, the built environment can be roughly interpreted in two ways: (1) as the physical composition of a space in which the materiality, forms, compositions, and orders are still understood as the major responsibility of designers, and (2) as the place where dynamic interactions between multiple actors (human, non-human, and other living creatures) happen.

Although both should not be understood as disconnected domains of interventions, the majority of contemporary practices tend to think of them as such.

If we are to consider design as a course of action, innovation as a process, and the built environment as a place where multiple actors are dynamically interacting, then design becomes the means through which innovation is continuously happening with the goal of improving the quality of existing interactions in relation to their fitness in the built environment.

One of the many ways designers can contribute is by building the capacity of continuous adaptation among the interacting actors. Yet, this can be challenged by principles of sustainability in which design should not be limited only to the interactions happening within the built environment, but also in the non-built environment.

Question 2

What are new engagement strategies that organizations can incorporate into the built environment?

The majority of the engagements between organizations were established through principles of linear economic models, in which limited resources are “taken, used, and wasted”. Arguably, these engagements are unsustainable because they inadequately consider the underlying connections between environmental, social, technical and economic concerns.

While new strategies to overcome this condition have gained traction in various sectors at the global level, including the circular economy movement, little attention has been given to (1) the complexity behind the interactions among local organizations and (2) the infrastructure required to promote such paradigm shift at the local level.

If the goal is to develop new strategies to increase the sustainability of the engagements between organizations, then new principles for establishing these engagements should be established, including considerations of the dynamics at the local level.

During the spring of 2018, we conducted a three-month research project on farmer’s markets in Chicago in collaboration with Plant Chicago. The goal was to understand how farmer’s markets could become a platform for advancing local circular economies.

Actors involved in the challenges argued that new types of values ought to be surfaced and exchanged among the organizations, and that inclusion, transparency, and diversity are the three main principles to inform such process.

We took one step further to understand how these principles should inform new engagement strategies, and we learned that strategies at the local level should be context-sensitive, and account for education, facilitation, collaboration, and coordination of the actors involved, given the desirable goals.

Question 3

With the increase in digitization, how should an organization start to think about user privacy in the built environments?

Just because certain types of data can be collected, it doesn’t mean that they should. The increase of digitalization in our daily lives raises several fundamental questions about how we individually and collectively make decisions, and how we should go about them when moving forward.

Issues related to privacy of individuals are intrinsically related to processes of democratizing decision-making, which ultimately challenges the ethics of existing power structures.

For example, several organizations are employing sensors in private and public built environments. While some of them are set to monitor environmental variables such as air pollution and water quality, others are being used to better manage and even inform interventions in these spaces.

In both cases, data belongs to and is controlled by few organizations, and information circulates between specific networks with their own agenda. Data is collected, cleaned, aggregated and maintained within infrastructures that the contributors themselves do not have access to or cannot influence decisions related to their personal interest and concerns.

Although organizations claim data is being anonymized and no “harm” is done to individuals or the environment, they are applying individuals and environmental data to their own interest without the contributors’ consent. In this context, organizations should establish new ethically sound infrastructures capable of assisting individuals in understanding and managing the data they have decided to share while empowering them to take actions considering the new information they have.

Question 4

With the increase in digitization, how should an organization start to incorporate a foundation to a sustainable way forward?

Public awareness about deteriorating environmental conditions (e.g. climate change), and social inequalities (e.g. social expulsions) are promoting significant transformations in organizations through digital technology and cultural change. Transformations aiming at promoting sustainability in such complex challenges require the comprehension of (1) the interactions among actors in technical, social and ecological infrastructures, and (2) the interconnectivity of the multiple systems in which organizations are involved.

While some of the forces involved in these requirements could not be understood in part due to the lack of technology, the contemporary increase in digitalization allows for seemly unrelated connections to be surfaced, introducing new canvas for organizations to make decisions.

However, many of them struggle to understand how these forces should be incorporated into their everyday practices as they lack adequate tools, the capability, and the structure to operate in the speed and dynamics in which actors are interacting with themselves and the environment.

If organizations are to incorporate new foundations to sustainable paths moving forward, they will have to create new mechanisms (including digital) capable of informing and understanding the dynamics of technical, social and ecological infrastructures as the condition for any future practice.

By doing so, they will be better equipped to make decisions and take the necessary actions towards sustainability. Nevertheless, they will have to challenge the contemporary bureaucratic and fragmented models in which they were created, and develop more interactive, nonlinear and open processes capable of engaging in the speed of continuous innovations being empowered by the digital technology.

Question 5

What are new ways of measuring the quality of life in a built environment?

Previous answers have carved the path to this one as they mentioned aspects of embedding sensors and data collection, the impact of digital technology, power structures, ethics, new infrastructures, and the integration of multiple systems given the dynamics of multiple actors.

Although new measurements of “quality of life” have been explored considering the incorporation of new information from the digital apparatus increasingly present in our daily lives (e.g. personal devices), all of the other aspects should inform new ways of understanding what a “good life” is, as well as what it could be in a given built environment. If we are to improve the conditions in which we live today, the debate around “quality of life” should not be limited to single narratives created by dominant structures trying to define what a “good life” is and how it should be measured. Rather, it should be understood as a relative and evolving cultural construct based on multiple references, whether they are new ones introduced by globalization processes, or traditional ones being passed from generation to generation through cultural heritage.

From this perspective, quality of life cannot be separated from the dynamics of daily lives (including the multiple dynamics in built environments) and their time frames; it has to be understood within an integrative, systemic approach that gives room for distinct values and beliefs to be considered, including the integrity of the ecological environments (including the built ones) where decisions are being made and impact is being generated.

This approach requires not only new tools for contextualizing and quantifying the quality of life (which I still have my concerns because sometimes aren’t measurable) but also to rethink the time frame being considered in the measurement process.

For example, the factors considered for measuring the quality of life in the food industry during the twentieth century were mostly based on principles of economic growth and greater access to (industrialized) food.

On September of 2017, the New York Times posted an article about the increase of obesity in Brazil due to the presence of big global businesses, and their impact on the local economy. The article references how the “new” offerings challenged traditional habits that nowadays are considered to be referenced for quality in life (e.g. local organic food). The increase of access to industrialized food decreased the quality of life of Brazilians by increasing their health issues. The impact goes beyond the health conditions of human beings as they also disrupted small local business, and produced more industrialized waste in the local environment.

Obviously, the speed in which large organizations were able to establish themselves in the Brazilian market overwhelmed its health, economic, and environmental services as the country found itself having to quickly accommodate the new unhealthy conditions in its built environment. This is an example of how the quality of life cannot be measured by single narratives of dominant structures, and have to be contextualized considering various values and beliefs in the equation, including integrated aspects of the socio-economic-ecological realm.

This blog was originally posted HERE.